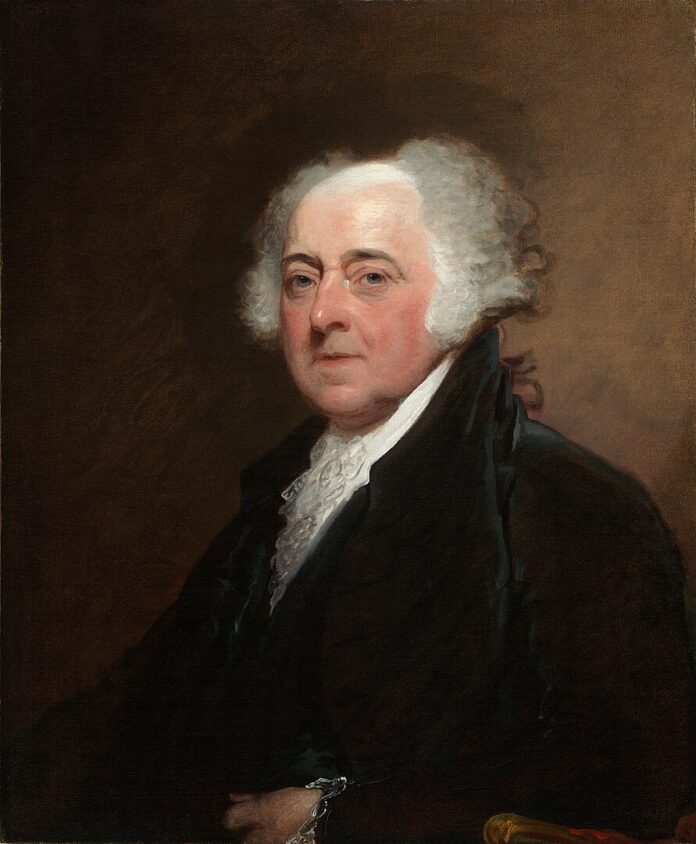

John Adams, the second President of the United States, was a key figure in the American Revolution, a defender of independence, and a founding father of the nation. Known for his unwavering commitment to justice, independence, and the rule of law, Adams played a significant role in shaping the United States. His career spanned from legal work to political diplomacy, and he served as both Vice President under George Washington and later as President from 1797 to 1801. This article delves into Adams’ life, his contributions to American independence, his presidency, and his lasting legacy.

Early Life and Education

John Adams was born on October 30, 1735, in Braintree, Massachusetts, to John Adams Sr. and Susanna Boylston Adams. Adams grew up in a modest New England family that valued education and hard work. He attended Harvard College, where he studied law, and developed a strong belief in justice and the principles of republicanism. Adams’ legal education and dedication to public service paved the way for his future career.

Adams began practicing law in 1758, and his commitment to defending the principles of justice soon gained him respect in the Massachusetts legal community. He became known for his integrity and willingness to take on challenging cases, even if it meant risking his popularity. One notable example was his defense of British soldiers accused in the Boston Massacre. Adams believed that everyone deserved a fair trial, and his successful defense of the soldiers reflected his deep respect for the rule of law.

The Road to Revolution

As tensions between the American colonies and Britain increased, Adams became an outspoken advocate for colonial rights. The Stamp Act of 1765 and the Townshend Acts of 1767 were met with strong opposition in the colonies, and Adams, along with his cousin Samuel Adams, became involved in the resistance movement. John Adams believed that the colonies should not be subjected to taxation without representation and that British policies violated the natural rights of the colonists.

In 1774, Adams was selected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, where he became a leading voice for independence. His persuasive oratory skills and commitment to the cause made him a prominent figure in the Congress. Adams helped shape the colonial response to British actions, advocating for resistance and unity among the colonies.

The Declaration of Independence

When the Second Continental Congress convened in 1775, Adams continued to push for complete independence from Britain. By 1776, the idea of independence had gained significant support, and Adams became part of the committee assigned to draft the Declaration of Independence, along with Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. Although Jefferson was the primary author, Adams played an instrumental role in promoting and defending the Declaration in Congress.

On July 2, 1776, the Continental Congress voted in favor of independence, and on July 4, the Declaration of Independence was adopted. Adams viewed this moment as a monumental achievement, recognizing that it would have far-reaching implications for the colonies and future generations. His dedication to independence and his work on the Declaration solidified his reputation as one of the founding fathers of the United States.

Diplomacy and the Treaty of Paris

During the Revolutionary War, Adams served as a diplomat, representing the United States in Europe. His diplomatic missions were crucial to securing support for the American cause. In 1778, Adams was sent to France to join Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee, where he worked to strengthen the alliance with the French government. Despite facing challenges due to his direct and sometimes confrontational style, Adams was determined to secure international recognition for the young nation.

Adams’ most significant diplomatic accomplishment came in 1783 when he helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris, which formally ended the Revolutionary War. The treaty recognized American independence and established favorable borders for the new nation. Adams’ work in securing peace with Britain demonstrated his dedication to building a strong and stable foundation for the United States.

The Vice Presidency

Following the war, Adams returned to the United States and became an advocate for a strong federal government. When the U.S. Constitution was adopted in 1787, Adams supported its principles and was elected as the nation’s first Vice President under George Washington in 1789. Adams served as Vice President for two terms, from 1789 to 1797.

Although the role of Vice President was largely ceremonial at the time, Adams found himself frustrated with the limited powers of the office. Despite this, he remained a loyal and supportive second-in-command to Washington. Adams presided over the Senate, where he cast 29 tie-breaking votes, more than any other Vice President in U.S. history. These votes often reflected his commitment to strengthening the federal government and establishing sound policies for the new nation.

The Presidency

In 1796, John Adams ran for President as a member of the Federalist Party and narrowly defeated Thomas Jefferson, who became Vice President. Adams assumed the presidency during a challenging time, as tensions with France threatened to lead to war, and domestic divisions between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans grew.

- The Quasi-War with France

One of the most pressing issues during Adams’ presidency was the conflict with France, known as the Quasi-War. The French government was angered by the United States’ neutrality in the ongoing conflict between France and Britain, leading to French attacks on American ships. In response, Adams strengthened the U.S. Navy and authorized the construction of new warships, but he resisted calls for a full-scale war with France.

Adams’ efforts to resolve the conflict diplomatically led to the signing of the Convention of 1800, which brought an end to the Quasi-War and restored peace with France. Although unpopular with some Federalists, Adams’ decision to pursue peace prevented a costly war and demonstrated his commitment to the principles of diplomacy.

- The Alien and Sedition Acts

Adams’ presidency was also marked by the controversial Alien and Sedition Acts, which were passed by the Federalist-controlled Congress in 1798. These laws allowed the government to deport foreigners deemed dangerous and criminalize speech critical of the government. Although Adams signed the acts into law, they were seen by many as an infringement on individual liberties and fueled opposition to his presidency.

The Alien and Sedition Acts intensified political divisions and strengthened the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson. Adams’ support for these measures damaged his reputation, and the acts became a source of controversy that followed him throughout his career.

The Election of 1800 and Retirement

In the election of 1800, Adams faced a fierce campaign against Thomas Jefferson, his former ally turned political rival. The election was one of the most contentious in American history, marked by personal attacks and intense party rivalry. Ultimately, Jefferson won the election, and Adams peacefully transferred power to him in 1801, setting a vital precedent for the peaceful transition of power in American politics.

After leaving office, Adams retired to his family home in Quincy, Massachusetts, where he spent his remaining years reflecting on his contributions to the country. He continued to correspond with many political figures, including Thomas Jefferson, with whom he eventually reconciled. The two founding fathers maintained a remarkable friendship until their deaths on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

Legacy

John Adams’ legacy is complex, reflecting both his unwavering dedication to American independence and the challenges he faced as a leader. He is remembered as a champion of justice, a diplomat, and a defender of American values. His role in the founding of the nation, his efforts to secure peace with France, and his work on the Declaration of Independence are among his most enduring contributions.

Although his presidency was marred by controversies like the Alien and Sedition Acts, Adams’ commitment to republican ideals and his insistence on peaceful transitions of power set important standards for future leaders. Today, he is celebrated as one of the key architects of American independence and a symbol of dedication to the principles of liberty and justice.

John Adams was a man of principle, courage, and intellect. From his early years as a lawyer defending British soldiers to his role in declaring American independence and leading the nation as its second President, Adams consistently demonstrated a commitment to justice and the rule of law. His life and legacy remind us of the importance of integrity in leadership and the enduring values upon which the United States was built.